|

| Joseph Kosuth - Self-described and Self-defined [1965] Foto - Sandra Guerreiro Dias, Museu Colecção Berardo, Lisboa [2014] |

Sunday, October 12, 2014

sem título

Wednesday, October 1, 2014

the portuguese eitghties, em todo o seu esplendor*

Tuesday, September 30, 2014

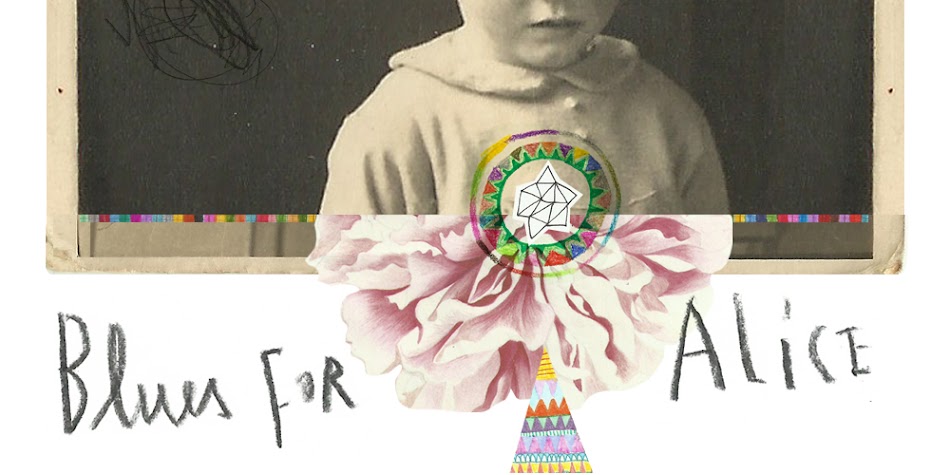

noite suja, noite de flores*

|

| the sleeping beauty |

|

| só à pedrada |

|

| o país criança |

|

| isto é que é cá um banquete |

Eis-nos chegados ao dia em que não temos nada para dizer. Esse dia que sempre chega e não é que seja mau de todo. Que o mesmo é dizer: de uma morte lenta e silenciosa. Que o mesmo é dizer que quando se fala de literatura, poesia ou do Mário Cesariny, que é tudo a mesma coisa, pouco há a acrescentar. Pois que o velho carqueja disse tudo o que havia para dizer e é explícito, o problema: por mais que o mundo dê muitas voltas, é às cambalhotas para o mesmo sítio. "Isso, ou um rosto", dirias, Mário. Um rosto esfacelado de poetas distraídos que não digam muitas coisas. Só o essencial, como uma fera. E ainda assim, sobre esta morte, que direi, Mário?

Direi que escrevo assim porque ele, Mário, que tenho por poeta, palhaço, crítico e performer, isso tudo ao mesmo tempo uma coisa e a outra sem se distinguirem, disse-me um dia que sonhava que voava lá muito alto e que, quando tinha medo das alturas, fazia de conta que a gravidade era uma espécie estrófica de muito silêncio lá dentro. Tudo passava. Será que passa, Mário? Será que a dorzinha que é menina, crónica de fazer malhinha, ou estas coceguinhas de gravatinha, da piadinha para a Joaquina, passa Mário? Pois que repara: a insurreição tornou-se moral. Vê lá tu. E que eu invente, tal qual como tu, não passa nada. Mais, para falar de poesia em Portugal, tem que se inventar muito que isto de mundos e fundos não é bem assim. A poesia não serve para nada e muito menos se for de barrete ou de alcochete, digo, de enfiada, para embilhar de assentada. Nem consta que alguma vez tivesse revolucionado as mentes, os pés ou as bocas de nação alguma. Que digo eu? Blasfémias. Ou então não, não era assim, que ele dizia, o Mário, cito:

'Meu caro Jorge de Sena (...) venho dizer-lhe que será de meu total desagrado a efectivação de tal anúncio, pelo que muito lhe peço e recomendo me não faça participar do novo ramalhete dos talentos. Como sabe, esteja eu certo ou errado - não é para discutir - são-me sumamente repelentes as alegrias excursionistas proporcionadas por esse tipo de assembleia nacional. Se não lhe faz um transtorno por aí além, prefiro solitário o meu próprio detrito - evola-se muito mais depressa sem acumulação por monturo nos terrenos baldios da capital. Creio, aliás, e isto é uma resposta à sua proposta de sugestções, que: antologias, só tendenciosíssimas, apaixonadamente tendenciosas, como seria de organizar algumas se entretanto não estivéssemos todos a morrer. Da inclusão do meu camarada António Maria Lisboa falará, como é óbvio, a sua própria obra. Pela parte que me toca no assunto, fecho-o com uma pergunta: será possível que você, Jorge de Sena, a ter lido o que António Maria Lisboa publicou, pense, presencisticamente, em incluí-lo, cadáver, poemas, ossos, tudo, em banquete tão sociedade de recreio e tão concomitante gracinha do meio editorial português?' Jorge de Sena não só incluiu os poetas em questão como lhes estabeleceu fichas biobibliográficas tão retorcidas como a cabeça dele. (Isto foi o Mário em 1958 a escrever ao Jorge de Sena e a pedir-lhe educadamente que o tirasse do 3º volume das Líricas Portuguesas. Está visto que o outro era teimoso que nem cornos.)

Não é verdade que estejamos todos a morrer, Mário. Há os que acham que não. Mas isso é só enquanto têm a ilusão que se se atirarem dum segundo andar, ganham asas e conquistam o céu, como tu. E se partirem a boca toda, é porque se esqueceram de a fechar. Vá, passo por esta poesia toda do pinguim ao papagaio porque estudo literatura e a literatura mata-me. A literatura aborrece-me, Mário. E a morrer, que seja de uma dor funda. Porque nem me aborrece de morte. Primeiro, porque tu já disseste tudo. Segundo, porque entre o pinguim e o papagaio, não se avista nada a não ser um horto de silêncio, como dizia o Al Berto mais ou menos mas sem a parte do incêndio. E segundo outra vez, porque para estudar aqueles que fumam cachimbo e trocam as pernas no programa da manhã a dizer piedades, escolho as tuas alarvidades e prefiro sempre as tuas perninhas, Mário, magrinhas, arqueadas, fininhas, sim senhor, de tanto envelhecerem e irem sozinhas, para casa ou outro lado qualquer, oh Mário. Mas desses como tu, não sobra mais nenhum. Foram tombando uns e umas atrás de uns e das outras, com os corninhos ao sol em efeito catadupa e uma sanidade mental meia chalada, incompreendidos e idas e corridas à pedrada, e à porrada, no país que era criança mas agora já não é, é adolescente e tem a mania.

Em todo o caso, Mário, que digo eu da minha justiça poética que não passa disso mesmo, uma forma de achar? Digo que não tem interesse nenhum que lhe chames gracinha, ao meio editorial português, porque assim eu fico sem nada. E já me basta nem circo, nem leões. E ainda assim, escrevo. Escrevo porque oito anos depois de morreres e as televisões terem acorrido ao teu funeral, vá lá, sabiam quem tu eras, a noite continua suja e há por aí umas flores de plástico. Retorcidas, ressequidas, sem cheiro ou graça nenhuma. E há quem meta de permeio e avental, outra vez a embilhar um poema a dizer que se vende. E ainda hão-de subir-nos ao palco a vender-nos a alma e a unta da cobra. Pois que há, e tu crês que sim. E tu vê lá que depois do "Au Tour des Livrées Sanglantes"**, se crê outra vez nisso. Não vai mal nenhum ao mundo que assim seja, já sei que dirias isso e até subias à cama de castanholas e vinho. Eu é que não estou para isso.

Isso ou uma morte que é dura: cadáver, poemas e ossos, tudo num banquete. Todos lambendo a tibiazinha. Já o meu avô dizia, quando lhe acenavam da morte, "mas isso agora é assim?". Pois não que não é! Os camelos. E tu Mário, faz-te à estrada, não te ponhas a amar que ainda te apanham e te fazem uma gala. Não que tu caísses ou bamboleasses. Mas já por aí andam aos salamaleques e tu não ias gostar nada que te fizessem do pescoço, um osso, que nem para joelho lhes chega o artelho.

Em todo o caso, estou bem contente que a crítica literária esteja morta e enterrada e a poesia e isso tudo, que morra tudo. Assim como a assim, recreio por recreio ou ramalhete por alfinete, de talentos ou unguentos, prefiro uma morte, ao sol. E que nos dês nas trombas numa manhã de outono com a tua alegria.

* - A. Breton

** - Manifesto dos surrealistas franceses escrito em 1957, por altura em que os dirigentes soviéticos desautorizam Estaline, onde se reafirma a separação do surrealismo face ao marxismo e se repudia veementemente o regime soviético.

Monday, September 29, 2014

Tuesday, July 15, 2014

The endless cycle of the portuguese eighties

|

| 2012 |

Cities recapture what they once were. Oblivion, the

dissimulated manifestation of any loss, is the unresolved ever-present

"endless cycle" (227). A Noite

das Mulheres Cantoras, one of the latest books of Lídia Jorge, is set in Lisbon in

the late 80's, representing the stage of a society saturated with

"presentism" (Hartog). This extraordinary tale(s) of five female

singers against the ephemerality of the "minute empire" (expression

that describes the dizzying speed of the roaring eighties) is an exercise of

"acknowledging the singularities" (Traverso, 2008) - "I go back

to the trivialities of the past and tie myself to their use" (30) - of the

collective history of the "realm of the ephemeral" (18) into which

post-revolution Portugal and post-war Europe in general were transformed. On

the one hand, these are the singularities of a group of women who are

"joyful because they are so sad" (152). On the other hand, these are

the singularities of a time without "any visible order" (312), of a

time of both celebration and mourning. They are described from the perspective

of Solange de Matos, the protagonist and first-person narrator. Although at

first sight the scenes show no causal relation between one another, they

interweave the thread of the narrative as they are bound together by

remembrance, absurd and the art of improvisation when faced with memory gaps.

In short, the narrative focuses on a woman's body - the narrator's and

simultaneously of all women - looking for a stage while straining against the

transcendence of the "limitless abundance" (310) and its underlying

oblivion - "If I insist on the oblivion issue, it is because maybe no

other issue has been this important" (229). Furthermore, the stage is also

the text, and the act of writing memory is the way of simultaneously

celebrating and putting on the show.

The plot: the eighties and a mysterious halo of

forbidden uncertainties, the beginning of "The Society of the

Spectacle" in Portugal, shortly after it entered the European Union.

Solange is a 19-year-old student who started the music group ApósCalipso

together with Gisela Batista, the Unstoppable Maestro, the Alcides sisters,

Maria Luísa and Nani, and Madalena Micaia, the black jazz singer. They intend

to change the world with their music - "We want to forget everything that

is behind us and to determine everything that is before us" (198). The

story focuses on the recording of their debut album and especially on their

rehearsals. In fact, a series of uncommon adventures takes on the narrative,

where laughter goes hand in hand with naked bodies on stage and catastrophe. To

be quickly forgotten is another feature of the "minute empire".

However, behind a curtain there is always an old looking glass - the other side

of the illusion -, which is also where the world ends and starts.

This tale is told 21 years after the "minute

night" or "Perfect Night", which refers to the night when the

main characters meet again in a live TV game show. The real threat is the past

- "Anyone who tries to reproduce it is a fool" (24) - which dictates

the need to tell. This is also the tale about what is left of that ghostly

realm of comfort and abundance - and over and over gets buried and resurfaces

-, because "the history of a group always reflects the history of a

people" (9). The well-kept secret of this group mingles with the one of

this "suspended world" (14) - impossible to disentangle from one

another -, namely Portugal in the eighties. In fact, its tragicomic history is

described as an "unstoppable mass of air" (202).

To a certain extent, the eighties were the time when

art took over the stage - "I believe we are on a stage and all

improvisation is allowed" (245). Lídia Jorge describes the memory of

several bodies in ecstasy taking on several stages: time, which is volatile,

reconstructed and facing oblivion; space, namely the city, here representing

the large stage of the profound social and cultural changes Portugal was undergoing.

These bodies are also transformed into spectacle, "dancer[s]" (281)

of memory and of the surrounding scenery, the "bright" city (150),

"full of junk and drifting papers" (197). However, a body vanishes.

Narrative is also a way of bringing into scene that empty space, filled by the

silence of practically all that is mute in history and in memory. In a body

brought back on stage, its disappearance stands out. Celebration or mourning?

There is no definite premise. Meanwhile, both coexist peacefully in this

"small minute world which Earth has become" (299). What one knows for

sure is that irony is also a state of exhilaration and that the text is the

balance or the art of (un)tidying up and making everything fall into place.*

* - publicado em Portuguese Literary & Cultural Studies, 25, 199-202.

Wednesday, July 2, 2014

Tuesday, June 17, 2014

Foi uma Festa!

|

| 33 |

|

| 14 |

|

| 78 |

|

| 43 |

|

| 56 |

|

| 89 |

|

| 17 |

|

| 57 |

|

| 43 |

|

| 28 |

|

| 67 |

.JPG) |

| 12 |

.JPG) |

| 99 |

|

| 44 |

.JPG) |

| 55 |

|

| 9 |

|

| 43 |

|

| 19 |

"Somos Todos Camões: Um Esbardalhamento Poético à Grande e à Portuguesa"

Performance Poética

Clube Recreativo dos Anjos

Lisboa

9/06/2014

Fotos: Ana García (à excepção de 12 e 99)

Edição: Sandra Guerreiro Dias (& fotografia 12 e 99)

Com:

Ana Carolina Martins

Bruno Ministro

Mário Lisboa Duarte

Nuno Miguel Neves

Ricardo Soares

Sandra Guerreiro Dias

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)